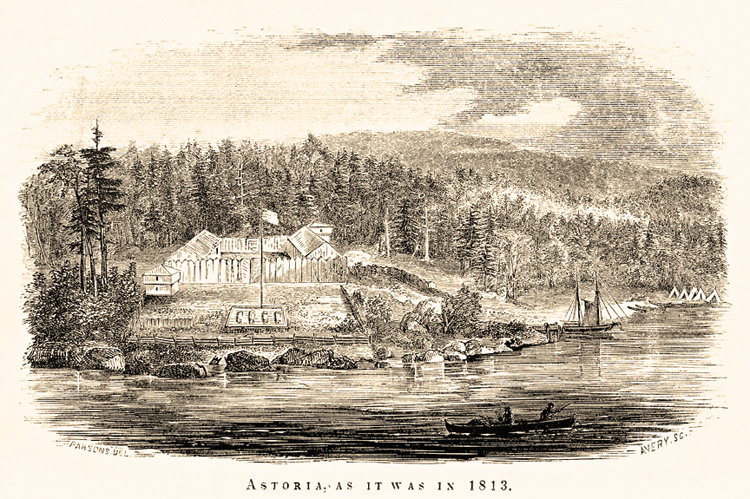

A Bird's-Eye View of "Astoria"

By Benjamin Fainstein, Literary Manager and Production Dramaturg

In Astoria, the real people of many nationalities who populated North America in the early 1800s become characters. So does the landscape itself, pitting both geographical and geological obstacles against John Jacob Astor’s drive to usurp control of the lucrative fur trade. Astoria is an overflowing treasure chest of history; this article offers a peek into the context of the world of the play and snapshot introductions to some of its fascinating inhabitants.

BEAVERS & THE FUR TRADE

The global fur trade dates back to the ancient world. Evidence of wool felting can be found in Homer’s Iliad, and felted beaver appears in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Beaver hats were so highly sought after that, by the year 1600, the European beaver verged on extinction due to aggressive hunting. Traders and trappers from France and England set their eyes on the North American species of beaver, which lived in abundance throughout the Great Lakes region and beyond. By the time Astor launched his venture in 1810, the market for beaver-derived goods promised enormous profit margins.

COLONIAL CARTOGRAPHY

Oregon didn’t look like Oregon in 1810. The territorial borders of North America changed hands throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as the Spanish, British and French empires fought for dominance and staked claims despite the established presence of Indigenous societies. The region was even home to a small but well-heeled Russian contingent, made up of wealthy nobles and their bands of fur trappers. By 1800, the young United States was geographically caught in the tumultuous crossfire of the major European powers. After the U.S. began receiving threats and economic sanctions from abroad, President Thomas Jefferson looked for ways to protect American citizens while developing the size and strength of the nation.

In 1762, France had ceded the massive Louisiana Territory to Spain; in 1800, Napoleon had strong-armed the Spanish into relinquishing control of the land back to France. In 1803, Jefferson was able to leverage Napoleon’s need to fund his military ventures against his inability to govern the Louisiana Territory from afar. Jefferson’s executive decision to purchase Louisiana for $15,000,000 planted the seed for U.S. expansion and economic ascendancy. Lewis and Clark immediately set out on their trek to the Pacific, and their journey confirmed for Jefferson and Astor that a transcontinental trade route across the wild Oregon Country, to which multiple nations laid loose claims, would play a crucial role in advancing the United States as a competitive world power.

Throughout the 19th century, the homelands and territories of many Native American nations and tribal communities were increasingly encroached upon. Between 1776 and 1887, 1.5 billion acres were seized from the continent’s Indigenous peoples. Natives and colonists had formed a network of delicate relationships during the two centuries before the Astorian expedition. Some had been mutually beneficial alliances; others had ended in distrust and catastrophic violence. Euro-Americans, among them Astor’s Overland Party, trekked through the domains of many of these communities on their way, including those of the Arapaho, Arikara, Bannock, Blackfeet, Cayuse, Crow, Dakota Sioux, Hidatsa, Iowa, Lakota, Mandan, Nez Perce, Otoe, Shoshone, Umatilla and Ute nations. As American citizens moved west in increasing numbers, the diverse Native populations, already decimated by foreign disease, were pushed into smaller and smaller corners of the continent.

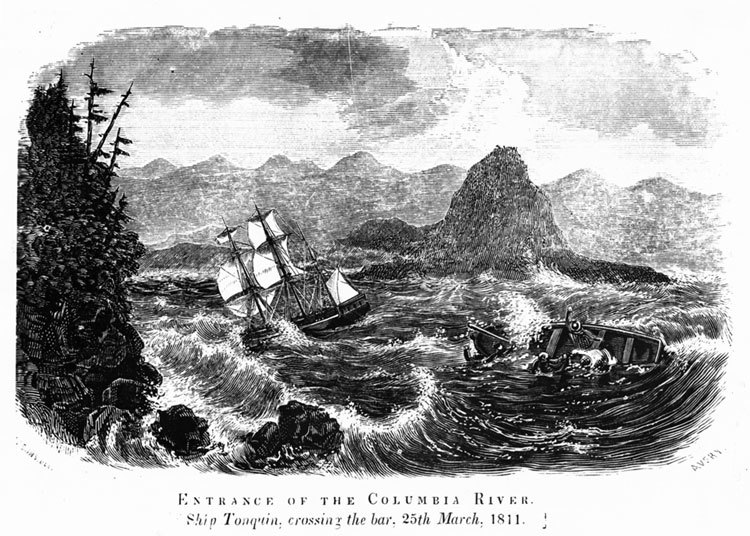

TREACHEROUS WATERS

To replenish its regiments, the British Navy was granted the power to “impress” men into service. When applied to British citizens, impressment was essentially a mandatory military draft. But the English also pressed foreigners at sea, an act of political piracy that resulted in the kidnapping of thousands of men who were forced to fight on behalf of their captors.

In 1807, British impressment of American citizens near Chesapeake Bay was escalating tensions to war, so President Jefferson signed the Embargo Act to prohibit American trade with other nations in the hope of gaining respect by cutting off foreign access to American resources. Jefferson’s policy had the opposite effect, however: the United States’ economy tanked as England and France took their business elsewhere.

The Embargo Act, which did little to mitigate British impressment, so weakened the American market that it was repealed in 1809, leaving Astor with a perfect opportunity to launch his expedition while the country clamored for new avenues to prosperity. Beyond the threat of piracy, the crew aboard Astor’s Tonquin faced a harsh life at sea, including diminishing food and water supplies, monstrous storms, cabin fever, and the mounting conflicts of leadership that dogged the party all the way to the Oregon coast.

THE VIBRANT VOYAGEUR

The Quebécois voyageurs who populate Astoria were masterful paddlers of swift birch canoes. The voyageurs spread from Montréal to Minnesota, and they worked tirelessly to shuttle goods from Europe to the North American hinterland and retrieve furs to send back across the Atlantic.

They were stocky, jovial fellows, who sang in polyphonic harmony throughout their 12- to 18-hour workday spent paddling the river at a rate of a stroke per second. At night, they smoked pipes, drank, danced, told bawdy jokes, and argued over who had acquired the most fashionable feathers to adorn his cap. With between eight and 14 men in canoes that varied from 20 to 40 feet in length, the voyageurs saw themselves as bands of brothers, robust in spirit, and their lifestyle was devoted to the fraternity they relied upon to survive.

TRAPPERS & MOUNTAIN MEN

The original “mountain men” of American lore date back to the years surrounding the Louisiana Purchase. The Overland Astorians encountered John Colter and Edward Robinson on their journey; these men had carved out a death-defying existence trapping fur in the Rockies, surviving in isolation with frequent assistance from Native communities like the Arikara and Shoshone. Colter was the first known white man to stumble across what is now Yellowstone National Park. The Kentuckian trapper Robinson, with his partners John Hoback and Jacob Reznor, had amassed a knowledge of the Bighorn Mountains that significantly aided the next generation of explorers.

The mountain man’s diet consisted almost entirely of meat, mostly bison, of which he would consume around 10 pounds per day without salt or seasoning. His daily life lacked any semblance of modern comfort: he was exposed to the elements, vigilant against possible threats at every turn, and found himself in extreme isolation more frequently than not. But the mountain men chose this life. They knew there were fortunes to be made from beaver fur, and they embraced the allure of surviving by their wits amid the majestic scenery of North America.

MARIE DORION & SARAH ASTOR

Social structures in 1810 restricted women’s rights and regulated their behaviors based on gendered norms of propriety. As a working class, biracial woman, Marie Dorion was held at arm’s length by multiple communities. She lived far from her childhood home and was bound to travel wherever her violent but devoted first husband, the translator Pierre Dorion, could find work. After his death, she used her wilderness expertise to survive until she was finally able to carve out a more prosperous life for herself.

Sarah Astor, by contrast, forged business partnerships with her husband at every turn. It was her dowry that allowed the young, poor John Jacob to get his instrument business off the ground, and it was due to Sarah’s foresight that the couple purchased huge plots of Manhattan real estate. She even negotiated a separate consultant salary for herself once her husband became dependent on her business acumen.

Sarah Astor and Marie Dorion, whose backgrounds and circumstances could scarcely differ more, stand as examples of women who, out of necessity or through personal ingenuity, challenged restrictive social structures to gain agency and some control over their circumstances.

CHINOOK COUNTRY

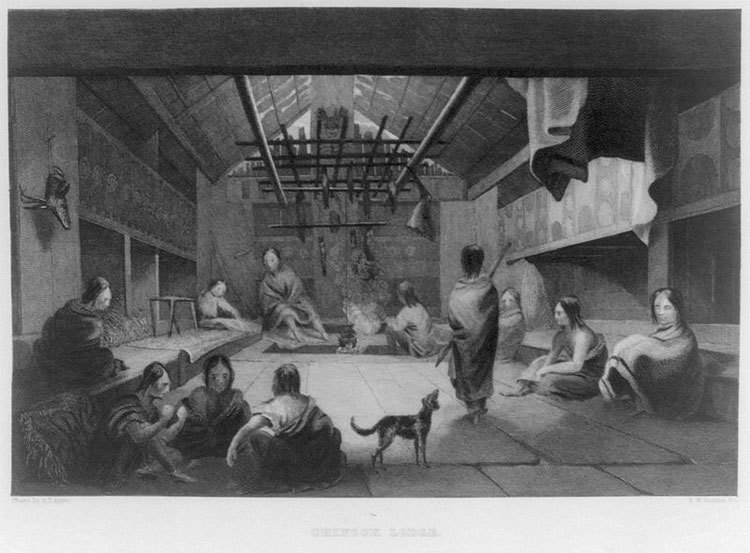

Soon after crossing the Columbia Bar, Astor’s crew encountered Native American inhabitants, many of whom were eager to establish civil relations and trading partnerships. Contact between the Indigenous population in the region and Euro-American explorers had been established decades earlier. Captain Robert Gray’s successful docking at the river’s mouth in 1792 — the docking which led him to name the river after his ship, the Columbia Rediviva — occurred close to a village called “Chinoak.” Gray, like Lewis and Clark and other white adventurers before them, mistakenly applied the name Chinook to all of the Native peoples living in the surrounding area. However, as the early 20th century Chinook leader Emma Luscier noted: “‘Chinook’ used to be just one place.” The region was home to dozens of autonomous yet interconnected societies, including those of the Chehalis, Chinook, Clackamas, Clatsop, Coos, Cowlitz, Kalapuya, Kathlamet, Klamath, Molalla, Multnomah, Shahala, Skilloot, Quinault, Tillamook, Walla Walla and Wasco. A pidgin version of the Chinook villagers’ language came to be known as Chinuk Wawa and allowed for intertribal communications. The language was particularly important for maintaining the flourishing system of trade into which Astor’s party stumbled and subsequently relied upon to survive.

The people nearest to the eventual location of Fort Astoria, who became the Astorians’ primary contacts, were the residents of Chinoak. Contrary to the Euro-American assumption that every tribe featured a “chief,” Chinook social structure did not necessarily dictate a sole leader; the community was grouped into a series of houses, each of which had a male head. Within each house, which ranged in length from 25 to 360 feet, at least two to five multigenerational families dwelled together, along with any slaves the families owned. Each house established its own internal hierarchy and distribution of labor, and the leaders of the most prosperous houses shared authority over the community. It is largely due to the guidance of Concomly, one of the leading Chinook headsmen in 1810, that the Astorian venture successfully navigated its early days amid mixed reception from local Native communities.

Following the War of 1812, leaders like Concomly and Coboway, of the Clatsop people, were excised from the trading deals white men were making with each other in the region. A few decades after the founding of Fort Astoria, they had lost control of their territory and economy. While the Chinookan peoples continued to live in pockets of their ancestral lands during American expansion, their populations dwindled throughout the 19th century. Today, many groups from the region belong to confederated tribal organizations and have been individually recognized by the U.S. government. However, the Chinook Nation, specifically, has yet to receive federal recognition.

Read more from our dramaturg: explore key dates of the Astor expedition.

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).