About Louisa May Alcott and her family

Louisa May

Born November 29, 1832 in Germantown, PA to Amos Bronson and Abigail May Alcott, Louisa May Alcott was the second of the four Alcott daughters. She spent the majority of her life between Boston and Concord Massachusetts. Her father, a visionary educator, ran Temple School in Boston and educated his daughters, and others, in progressive ways for the time. His friends and Louisa’s teachers were notable writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Theodore Parker and Henry David Thoreau.

Because of Mr. Alcott’s desire to innovate, he often found himself with impractical or unreliable sources of income. For example, he founded the failed Fruitlands — a utopian community — losing a large portion of the family’s money with it. Louisa felt responsible for caring for the family in ways she thought her father incapable. At 15 she wrote”

“I will do something by and by. Don’t care what, teach, sew, act, write, anything to help the family; and I’ll be rich and famous and happy before I die, see if I won’t!”

And she did — she worked several jobs as a teacher, a governess, a seamstress and a domestic for many years before she found writing.

Alcott’s early stories were penned under pseudonyms including A.M. Barnard, an intentionally genderless offering which would leave readers and publishers alike to believe that she was a man. Those stories were often lewd and violent but lucrative for the young writer. Her first book of short stories, Flower Fables, was published under her own name in 1854.

In 1861, Alcott desired to join the war effort. The Alcotts were staunch abolitionists. Louisa later recounted that one of her early childhood memories was of a ‘Contraband’ slave, hiding in their home on their way to Canada. If she’d had her way, she’d have enlisted and fought for The Union. Instead, she sewed uniforms until she was old enough to join the army nurse corp. In 1862, she joined famed nurse Dorothea Dix’ U.S. Sanitary Commission and worked in the Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown. Alcott’s duties included cleaning wounds, feeding men, assisting with amputations and organizing patient wards. She’d intended to serve for 3 months in the post but six weeks in, she contracted typhoid and was sent home. Upon her return, she wrote and published the novel Hospital Sketches based on her time with the Union Army and the letters she’d sent home to her family.

Of Hospital Sketches Louisa wrote “the Sketches never made much money, but showed me ‘my style’, and taking the hint, I went where glory awaited me.” This style — loosely autobiographical, full of stories and correspondence between the Alcott family — brought her glory indeed when in 1868 her publisher encouraged her to write a “girl’s story.” In three months, Alcott wrote 402 pages that resulted in Little Women, Part I. In 1869 Alcott was able to write in her journal: “Paid up all the debts…thank the Lord!” She followed Little Women’s success with two sequels, Little Men: Life at Plumfield with Jo’s Boys (1871) and Jo’s Boys and How They Turned Out (1886).

Louisa May Alcott spent the majority of the 1870s and 80s in Boston and Concord caring for her niece and namesake Lulu who had been left in her care after her sister’s death, and for her ailing parents. Her mother passed away in 1877. 11 years later, Amos also died. Louisa lived just two days after her father’s passing. She never married or had children of her own.

Amos

Louisa’s father was born in November 1799 in Wolcott, Connecticut. The son of a flax farmer, he taught himself to read and eventually became an educator. As a leader in the Transcendentalist Movement, he brought music, art, nature and physical education into the classroom — a novel idea for education at the time. From 1859-1864, Amos served as the Superintendent of Schools in Concord, Massachusetts. He also started a summer school for adult learners that lasted for nearly a decade until his death in 1888.

Abigail May

Louisa’s mother was born in October 1800 to a prominent New England family. Her great aunt, Dorothy Quincy, was married to John Hancock — the first governor of Massachusetts and noted signer of the Declaration of Independence. She devoted herself to her family and to social work — working to advance such causes as abolition, women’s rights and temperance. One of her most famous quotes to her daughters, who she encouraged to pursue their talents and desires, was “Hope and keep busy”. She lived until November 1877.

Anna

Louisa’s sister Anna, the inspiration for Meg, was born in March 1831. Despite her being the most traditional member of the Alcott family — eventually becoming a devoted wife and mother — she was also quite devoted to theater. She had secret longings “to shine before the world as a great actress or Prima Donna.” She and Louisa formed the Concord Dramatic Union in 1858. There she met John Bridge Pratt and the two fell in love while playing opposite of each other in The Loan of a Lover. John died in their 10th year of marriage, leaving her behind with two young sons. She lived out the rest of her days in the house she and Louisa purchased in 1877.

Elizabeth

Elizabeth, the inspiration for Beth March, was born in 1835, and like her literary counterpart, died after a complication from contracting scarlet fever. She was 22 years old. She loved kittens, playing the piano and sewing. The descriptions of Beth in Little Women are said to be an accurate portrayal of the beloved member of the Alcott family.

Abba May

The youngest of the Alcott daughters, Abigail was born in 1840. Like Amy in Little Women, she was a talented visual artist. She began her art studies in Boston and after the success of Louisa’s novel, she was sent to study in London, Paris and Rome. In 1878, after several successful art exhibitions, she met and married a Swiss businessman, Ernest Nieriker. The couple lived in a suburb of Paris, Meudon, and had one daughter named after Louisa, who they called Lulu. Just 7 weeks after Lulu’s birth, Abba died and Lulu was raised by Louisa in Concord.

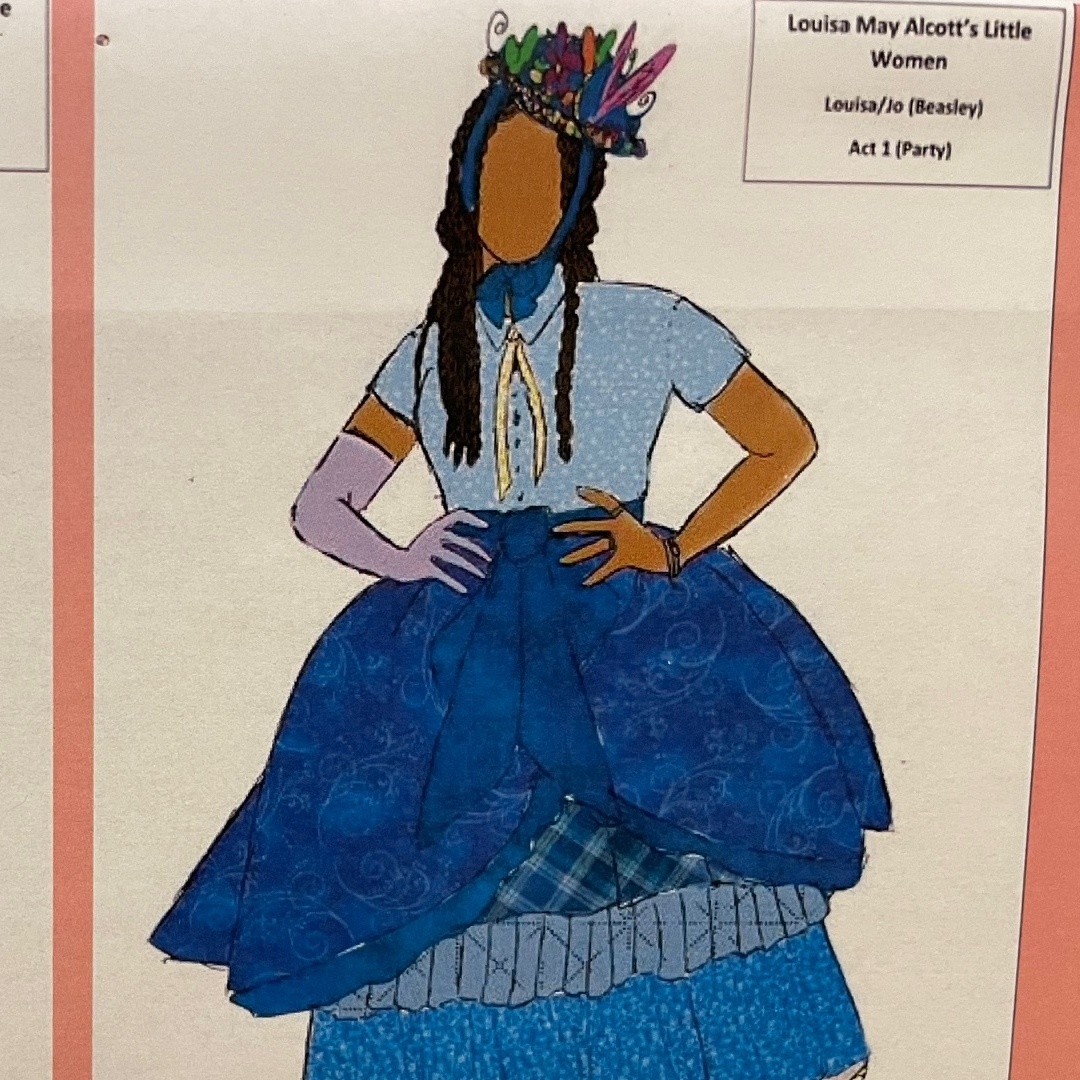

Preview Image Details

(information about the image that accompanies links to this page)

Costume rendering by designer Lucy Wells

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).