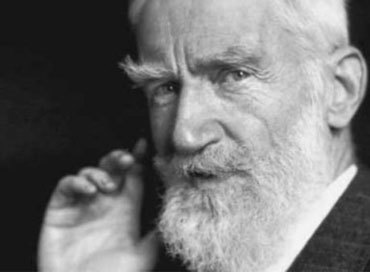

Shaw and Film

Though a famous playwright and drama critic, George Bernard Shaw had long been fascinated by film. He happily appeared in newsreels and had even been a member of the London Film Society. While Shaw loved film, however, he hated his own work on the screen. He’d been singularly unhappy with an operetta of Arms and the Man, called The Chocolate Soldier. And he rejected plans to turn Pygmalion into an operetta. But when Gabriel Pascal came along, with his personal fervor for Shaw’s art, he charmed the playwright and won Shaw over with his frank admission of being flat broke. Shaw apparently appreciated his honesty and agreed to a film of Pygmalion.

It took Pascal nearly two years to put the production together, and what he ended up with was something of a miracle—born partly of inspiration and partly of luck, owing to the recession that had left a major portion of the British film industry idle, including some important young talents, among them director Anthony Asquith and editor David Lean. The other key elements lay in a young actress named Wendy Hiller, whom Shaw had seen onstage and who would play Eliza Doolittle, and, in the starring role of Henry Higgins, the international box-office draw Leslie Howard, who would also serve as codirector with Asquith; Shaw didn’t think Howard was right for the part, being too appealing, but saw him as necessary to draw audiences. The real secret to getting Pygmalion (1938) made, however, was Asquith’s persuading Shaw to change the play, by creating the embassy ball scene (which, true to Shaw’s sense of humor, included a little satirical portrait of Pascal, in the person of the conniving Hungarian elocution expert, Karpathy). That scene, and the ending implying a possible relationship between Eliza and Henry, added an emotional hook to the Shavian wit and the playwright’s ideas about language and class that put the film over with audiences around the world.

The great success of Pygmalion proved that Shaw’s work could be brought to the screen to the satisfaction of the playwright, producers, and the public. And in its wake, Shaw granted Pascal the right to make films of any of his plays, an agreement that would result in three more projects and an extraordinary creative relationship between the Fabian socialist and the theatrical eccentric, both relatively new to the world of cinema. Their voluminous correspondence concerning the plays and the films (much of which had been thought lost, but which in recent years has started to appear in publication) reveals a unique devotion to each other’s goals.

Major Barbara came three years after Pygmalion and was made under vastly different circumstances. England was now at war, and rather than being underemployed, many of the most talented people in the British film industry were working full-time, either in the business or in the armed forces. The project was in production through the difficult year of 1940, with German air raids disrupting filming. Andrew Osborn, originally to have played Adolphus Cusins, was called up for service and replaced by Rex Harrison. Actor Donald Calthrop, who portrayed Peter Shirley, died of a heart attack on July 15. And yet the film ended up an extraordinary achievement, for reasons that weren’t obvious to most observers at the time.

Major Barbara came three years after Pygmalion and was made under vastly different circumstances. England was now at war, and rather than being underemployed, many of the most talented people in the British film industry were working full-time, either in the business or in the armed forces. The project was in production through the difficult year of 1940, with German air raids disrupting filming. Andrew Osborn, originally to have played Adolphus Cusins, was called up for service and replaced by Rex Harrison. Actor Donald Calthrop, who portrayed Peter Shirley, died of a heart attack on July 15. And yet the film ended up an extraordinary achievement, for reasons that weren’t obvious to most observers at the time.

Officially, Major Barbara was produced and directed by Pascal. In reality, Pascal relied on two “assistants”: David Lean and Harold French. Lean had had his career breakthrough as a film editor (and very nearly a codirector) on Pygmalion, and in the three years since had gone to the top of his profession, and was about to make the official leap to the director’s chair; French was an actor turned director who’d had an immense stage hit with Terence Rattigan’s French Without Tears in 1937. In French’s description, Pascal would walk around the set, yelling instructions and waving his arms. But in terms of what showed up on-screen, French worked with the actors on their dialogue while Lean dealt with such matters as camera placement and the devising of shots. And between them—with Shaw himself on the set, as well, for much of the shoot—they made an amazingly dexterous and entertaining motion picture, especially given the density of ideas being traded among characters.

In some ways, Major Barbara could be considered a distant cousin of King Vidor’s The Fountainhead (1949), another fiercely intellectual drama, adapted by Ayn Rand from her novel. The two authors aren’t often compared as creative figures, Shaw being a socialist while Rand’s work is steeped in a reverence for the idea of the individual against the collective (i.e., anti-Communism), but both were polemicists—Shaw often wrote explanatory introductions to his plays that were longer than the plays themselves, and Rand is famous for her philosophical tracts, as well as for extended speeches voiced by key characters in her novels. Both films are populated by figures who, to varying degrees, function more as spokespersons for (or embodiments of) their creators’ ideas than they do as dramatic characters. Of course, Major Barbara offers more wit in a single line than Rand would infuse into the whole of her work.

Major Barbara was, indeed, criticized in some circles in 1941 for being overly long and talky. But the passage of time and the gradual dumbing down of most cinema have only made the film seem more clever, even sprightly at times. And it was a box-office success, if not quite to the extent of Pygmalion.

Major Barbara marked the peak of Shaw’s direct involvement in film. The playwright was so enthusiastic during production, in fact, that he actually ran onto the set amid the extras during the staging of the Salvation Army rally, interrupting the shot. He made nineteen major changes to the play, each of them based on a serious consideration of the needs of visual storytelling, most notably the rally and the tour of the Undershaft & Lazarus factory, a cinematic tour de force accompanied by a rousing score by William Walton. The resulting mix of visuals, music, and performances, especially those of Wendy Hiller, Robert Morley, Robert Newton, Donald Calthrop, and a young Deborah Kerr, made Major Barbara, philosophizing and all, alternately dazzling, charming, and engrossing entertainment.

Thanks to the glorious world of the internet, Shaw is no longer a Victorian era relic, but a living, breathing — and funny! — person. Check out these vintage "home videos" and get to know the man yourself.

This footage of George Bernard Shaw filmed immediately after arriving for his first visit to Capetown, South Africa shows Shaw's great oratory skills and downright silliness. The film's original caption says captures his levity and wit perfectly, "Incorrigibly humorous as ever! The great dramatist 'pulls our leg' delightfully."

On his 90th birthday, George Bernard Shaw, dressed in knee breeches and wide brimmed Stetson hat, leaves his house to walk in garden. He enters his small writing shed at the bottom of the garden which he uses for a study, showing off his desk and portable typewriter. Pretty spry for a 90-year-old!

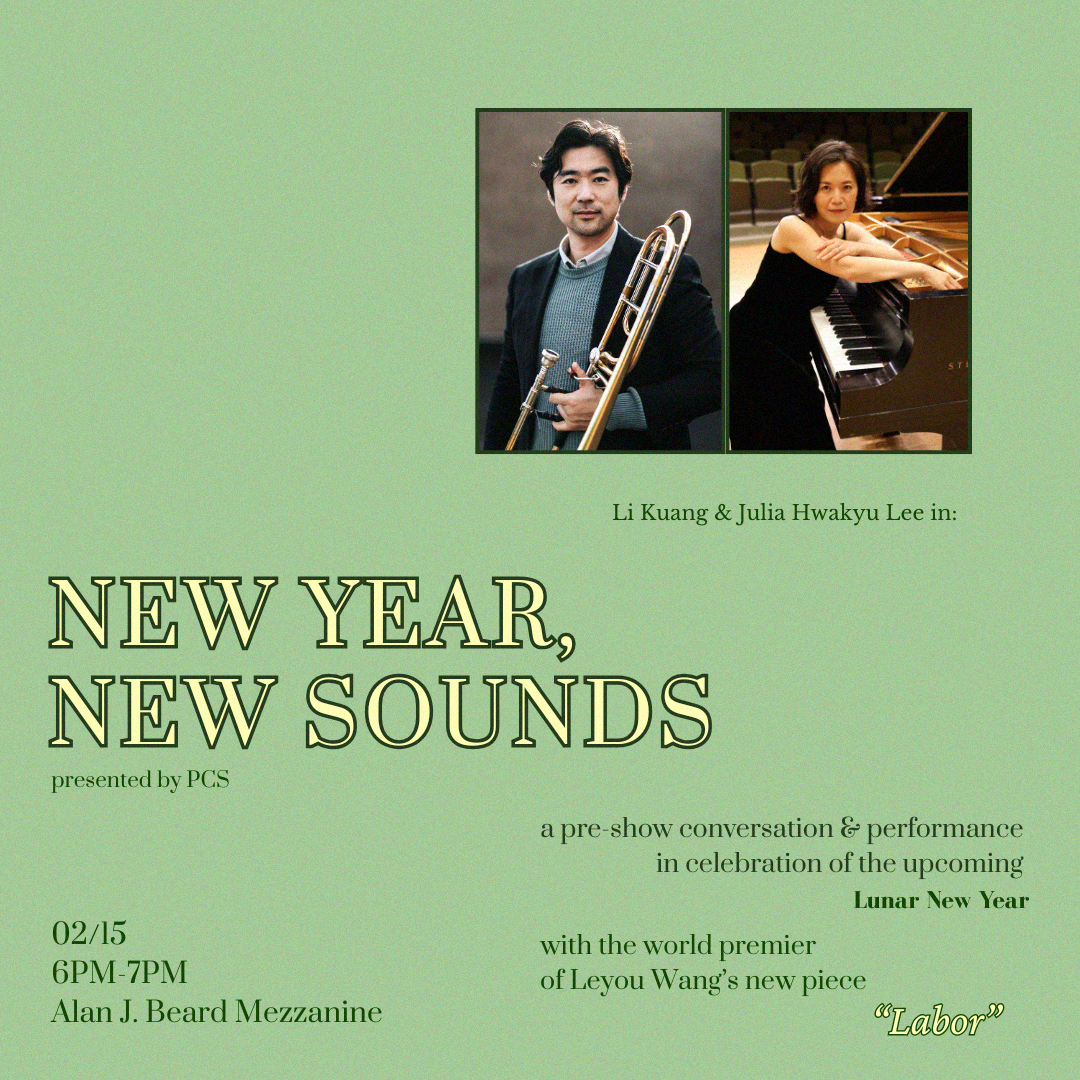

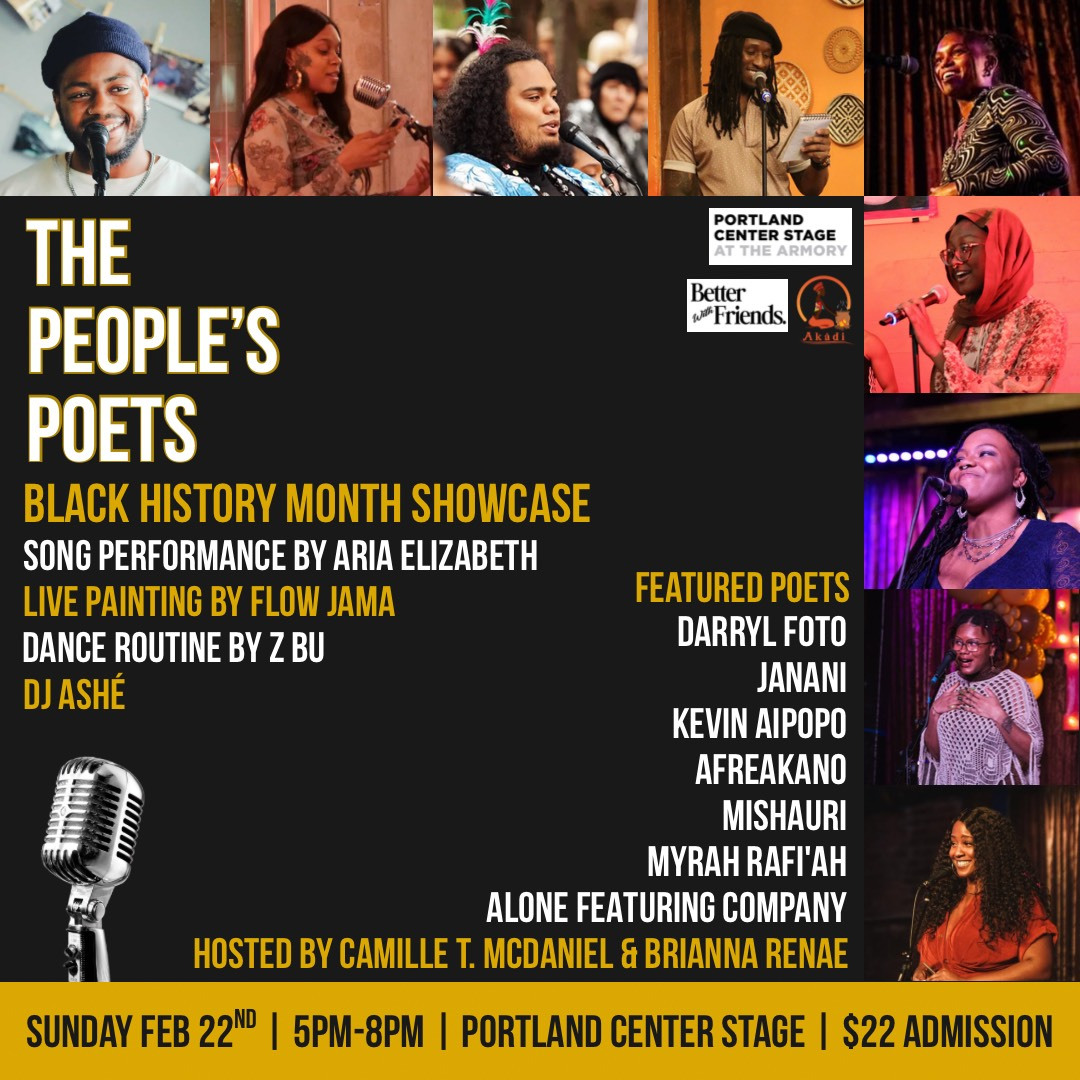

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).